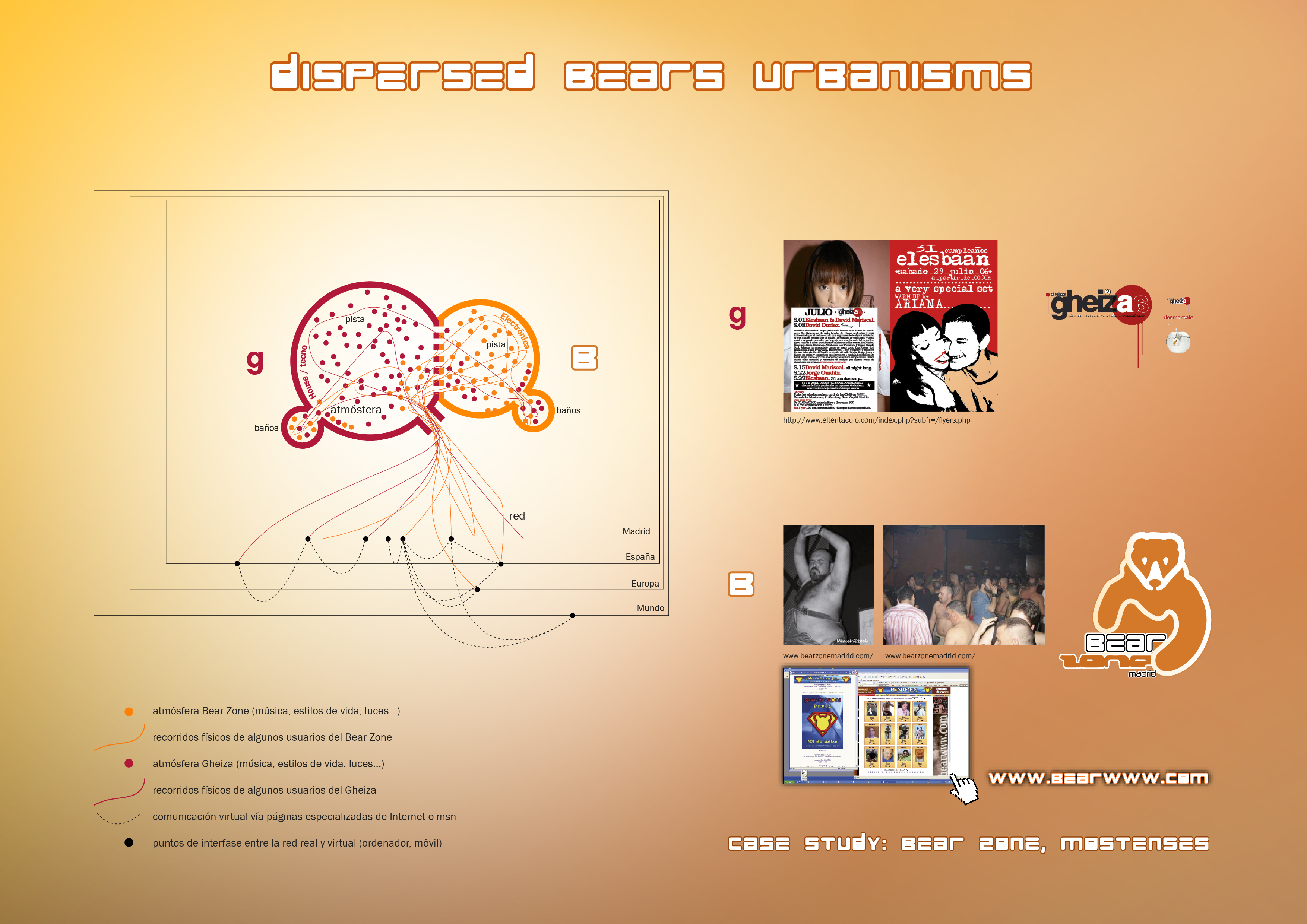

When we migrated from

Rotterdam to Madrid in 2003, after studying the urban developments within the

Cape Verdean diasporic community, we continued to explore what we referred to

as “dispersed urbanisms”, which means urban environments that operate

at various levels (multi-scale) and through different types of physical and

virtual channels (multimedia). We found it particularly interesting to study

dispersed urban environments that were close to us but often overlooked in

urban studies. Possibly this neglect occurred because these urbanisms were

linked to communities that were also overlooked. For example, the

configurations that emerged around the gay bear community, in which we used to

be involved. Their spaces and networks provided us with valuable insights. One

of the reasons was that they challenged the traditional interpretation of

concepts like “public space”, which is commonly regarded as the main

location for interactions between different groups. They demonstrated the

societal significance of other physical-virtual locations that functioned in a

similar manner, albeit with distinct spatial features.

For example, the spatial configurations around some

nightclubs generated very specific forms of encounter between the bear

community and other urban tribes. To comprehend the territory of those

communities, it was important to consider not just the physical space, but also

how it was articulated through virtual spaces. For example, contact websites

such as bearwww.com were very important. While this

site was mainly used for dating, it was also used for other purposes such as

renting rooms or looking for a job (Diego Barajas, “El espacio urbano para

las prácticas creativas como interfaz hacia otra globalización y el habitante

como constructor de la ciudad”, in N. Aramburu (ed.), Un lugar bajo el

sol, Buenos Aires, CCEBA-AECID, 2008, p. 114-115). Classic books

like “Queer Space” by Aaron Betsky (1997) or the works of Jan

Kapsenberg with Bart Lootsma, who was our professor at the Berlage Institute

(2000-2002), served as pioneering references for us in our research endeavors.

At that time there were very few examples of queer culture in architecture and

urbanism.